G. Beegan, P. Atkinson & D. Sugg Ryan, Ghosts of the Profession

Special Issue of the Journal of Design History 21(4), 2008.

Professionalism, amateurism and the boundaries of design

Gerry Beegan and Paul Atkinson

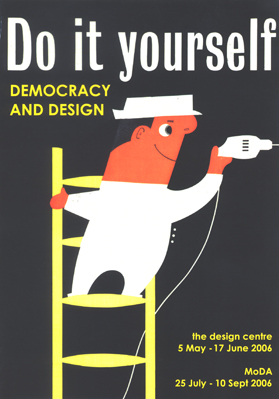

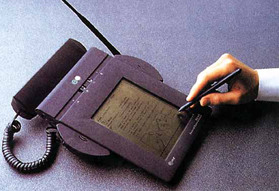

The focus of this special issue is the constantly changing relationships between amateur and professional practice during the last century or so, over the course of the ascent of modernism in design. In Europe and the United States this period has seen the emergence and growth of the design professions and concurrently the development of design practice as an unpaid undertaking in myriad forms from handicrafts, to DIY, to digital tinkering. Given the porous nature of the boundaries between professional and amateur, this introduction does not attempt to define once and for all these slippery terms. Indeed, the Special Issue demonstrates that it is impossible to do so. Rather, it examines the themes of influence and alterity that recur in design in diverse locations, periods and practices. As we shall see the terms amateur and professional can have positive and negative connotations and are often contrasted with each other.

As a whole, the special issue demonstrates that professional and amateur practice are always connected, even when the relationship is one of repudiation. Professional practice defines itself by its distance from the unschooled practitioner yet, as the essays in this collection demonstrate, the vernacular is an inescapable part of modern design. At the same time, the professional is often a categorization that amateur designers reject, as a limitation to their creativity or originality. These essays look at the conscious appropriations of vernacular design by professionals and at the rejection by amateurs and working designers alike of professional specialization. They emphasize the complexity of the interchanges between the professional designer and the dilettante, the amateur and the vernacular maker. Professional organizations, educational standards, journals, systems of licensing are instruments through which professions try to define themselves. In the design professions this self-definition is a continual struggle, in part because everyone engages in design through the quotidian choices we make, from the font and type size in which weset an office notice to the color we paint our homes.

The special issue can be accessed from Oxford University Press here: